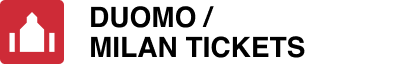

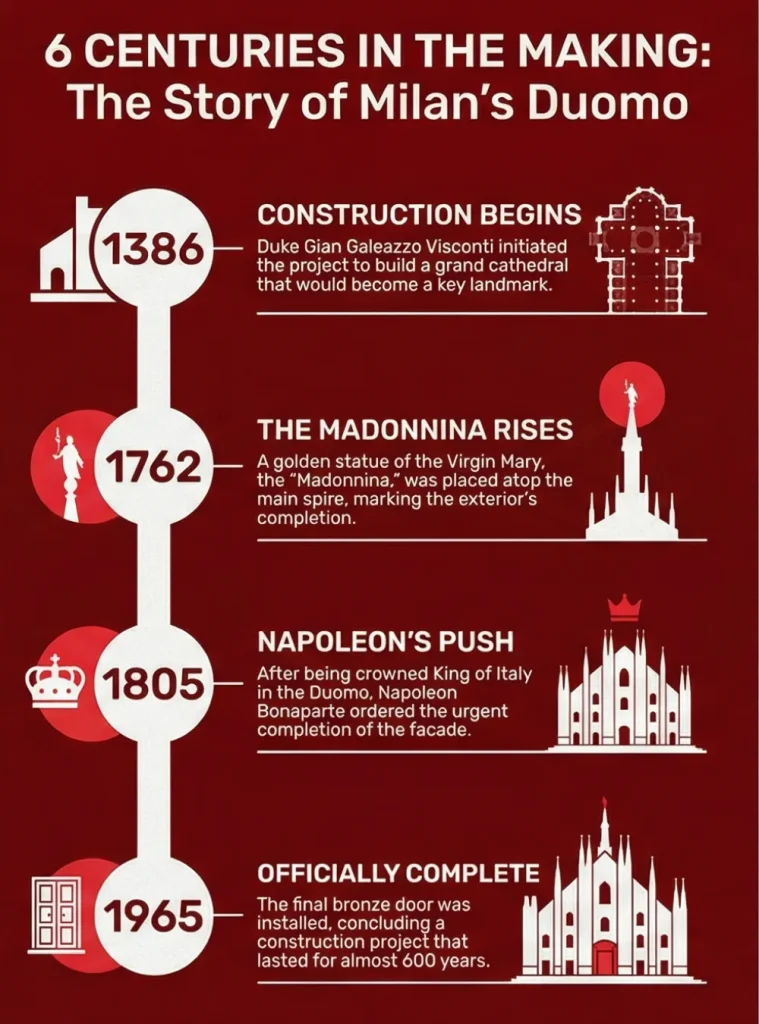

The history of Duomo Milan is a six-century architectural timeline that began in 1386 under the patronage of Duke Gian Galeazzo Visconti and Archbishop Antonio da Saluzzo.

The Duomo Milan has a long history that stretches across many centuries. His timelines is:

During the 15th century, the construction of the Duomo Milan made significant progress. The cathedral’s structure grew and the detailed facade with its spires and statues started to form. Famous artists and architects like Leonardo da Vinci, Andrea Pisano, Arnolfo di Cambio, Filippo Brunelleschi, and Giotto contributed ideas to the design making the Duomo even more artistically rich. By 1762, the golden statue of the Virgin Mary known as the Madonnina was placed on top of the main spire. This marked the completion of the cathedral’s exterior.

The Duomo di Milano was built over a span of nearly six centuries, with construction officially beginning in 1386 under Archbishop Antonio da Saluzzo. While the cathedral’s main façade was finished in 1813 by order of Napoleon Bonaparte, the structure was not considered fully complete until the final bronze door was installed in 1965.

The construction of the Milan Duomo began when Archbishop Antonio da Saluzzo and the Lord of Milan, Gian Galeazzo Visconti, decided to build a cathedral that would surpass any other of the era in grandeur.

However, the main façade wasn’t completed until 1813, under orders from Napoleon Bonaparte, who wanted to be crowned King of Italy in a finished cathedral that would symbolize his power. But even after this, work continued: the last bronze door was installed in 1965.

So, if you’re wondering how old the Duomo in Milan is, the answer depends on which part you’re looking at: the building has more than 635 years of history since its first foundations, though technically it wasn’t considered completely finished until the mid-20th century.

The interior of the Duomo is characterized by 52 monumental columns supporting the vaults and illuminated by historic stained glass windows. Key features include the Crypt of San Carlo Borromeo located beneath the main altar and the Duomo Treasury, which houses a collection of medieval reliquaries and sacred liturgical ornaments.

On the other hand, the Duomo Terraces are a rooftop observation area providing 360° panoramic views over Milan and the Alpine arch. Accessible via elevator or a 250-step staircase, the roof allows for close inspection of the cathedral’s Gothic architecture, which includes over 3,400 marble statues and spires.

As for the Duomo Museum, located in the Palazzo Reale facing the cathedral, it houses an impressive collection of original sculptures, tapestries, stained glass, and models documenting the temple’s construction. It’s an essential stop if you want to understand the artistic details and techniques used throughout the centuries.

For lovers of ancient history, the archaeological area helps you understand Milan’s Christian origins. Beneath the current cathedral lie the remains of the Baptistery of San Giovanni (4th century) and the ancient basilica of Santa Tecla, where Saint Ambrose baptized Saint Augustine in the year 387.

Finally, many tourists overlook the Church of San Gottardo in Corte, connected to the Duomo complex. This small 14th-century temple, with its elegant octagonal bell tower, was the private chapel of the Lords of Milan and preserves frescoes of great historical value.

Our recommendation for an optimal visit: start with the interior and crypt to understand the spiritual dimension of the place, continue with the terraces to enjoy the views (preferably at sunset), and finish at the museum to delve deeper into the details you’ve just seen. Set aside at least 3-4 hours if you want to experience it calmly and without rushing.

The Duomo’s construction was a collective project that involved dozens of architects, engineers, and master builders over nearly six centuries.

The initial project in 1386 was under the direction of Simone da Orsenigo, the first chief engineer, who established the foundations of the Lombard Gothic design. However, debates soon arose about how the work should continue, leading to the hiring of French and German architects specialized in international Gothic, such as Nicolas de Bonaventure and Jean Mignot.

The latter, who arrived from Paris in 1399, led intense technical discussions with the Lombard masters about the building’s structural stability. In fact, the foreign architects questioned whether the cathedral could support its own weight, generating one of the first documented architectural debates in history.

Looking at the history with perspective, we see that figures like Filippino degli Organi, Giovanni Antonio Amadeo (who worked on the tiburio), Pellegrino Tibaldi in the 16th century, and later Carlo Buzzi and Francesco Maria Richini in the 17th participated in the construction. The neoclassical façade was finally completed by Giuseppe Zanoja and Carlo Amati under Napoleonic supervision in the early 19th century.

So when someone asks you who built the Duomo di Milano, the correct answer would be: entire generations of architects, sculptors, and artisans who turned this cathedral into an authentic multigenerational project where each era left its mark.

Duomo Milan is an exceptional example of Gothic architecture, but with a very particular twist. While French Gothic is characterized by its extreme verticality and structural austerity, the Duomo’s Lombard Gothic incorporates a decorative profusion that makes it unique.

The cathedral combines elements of international Gothic with Renaissance and neoclassical influences, especially visible in the main façade. This mixture of architectural styles reflects the centuries of construction: what began as a pure Gothic project in the 14th century evolved according to the trends of each era.

The most evident Gothic characteristics include the exterior flying buttresses, the ribbed vaults that distribute weight toward the columns, and the vertical spires that seem to defy gravity. However, you’ll also find Renaissance elements in some side chapels and, of course, the clear neoclassical influence on the façade, completed under the Napoleonic taste of the 19th century.

Despite this mixture, the Duomo maintains a surprising visual coherence. The pink-white marble that covers the entire structure acts as a connecting thread that unifies the different styles into a single monumental architectural vision.

One of the Duomo’s most distinctive elements is its pink and white marble from Candoglia, extracted from quarries located near Lake Maggiore, about 100 kilometers from Milan. This material wasn’t a casual choice, as Gian Galeazzo Visconti granted in 1387 the exclusive and perpetual use of these quarries for the cathedral’s construction, a privilege that continues to this day.

Back then, the marble was originally transported via the Naviglio Grande, the canal system that connected the quarries with Milan, in barges marked with the initials “AUF” (Ad Usum Fabricae, “For use of the Factory”), which granted them tax exemption. This same expression gave rise to the Milanese expression “a ufo,” meaning “for free.”

It’s important to note the aesthetic contribution of this marble: its pinkish tone gives the Duomo a unique warmth among European Gothic cathedrals, which are usually built in dull gray stone. Additionally, this material has the peculiarity of slightly changing color depending on the daylight, which means that at dawn and dusk, the cathedral seems to glow with golden and reddish tones, creating an unforgettable visual spectacle.

Even today, restoration and maintenance work continues to use exclusively marble from the same Candoglia quarries, guaranteeing the aesthetic continuity of this monument through the centuries.

The Milan Duomo’s silhouette is unmistakable, and that’s mainly due to its “marble forest”: more than 135 spires and pinnacles that rise toward the sky like a crown of stone. Each spire is crowned by a statue, creating a sculptural landscape that surrounds you when you walk on the terraces.

The flying buttresses are structural elements of Gothic architecture that serve a crucial function: they transmit the weight of the interior vaults toward the building’s exterior, allowing for thinner walls and larger windows. In the Duomo, these flying buttresses are profusely decorated with sculptures, becoming artistic pieces in their own right.

The tallest spire, the central tiburio, reaches 108.5 meters in height and was completed in 1774. At its summit stands the famous Madonnina, the golden statue of the Virgin Mary that has become Milan’s quintessential symbol. From 1774 until the mid-20th century, there was an unwritten law that prohibited building structures taller than the Madonnina, to keep her as the city’s highest point.

Each spire, each pinnacle, is crafted with the same level of sculptural detail, even in parts that aren’t visible from the ground. This reflects the medieval philosophy that architectural perfection had to be absolute, as it was directed not only to human eyes, but also to God’s.

The Duomo’s main façade is probably its most controversial element from an architectural standpoint. While the rest of the building is Gothic with exuberant decoration, the façade presents much more sober neoclassical lines, the result of Napoleonic intervention in the 19th century.

For centuries, the façade remained unfinished, partially covered with bricks and provisional elements. It wasn’t until Napoleon Bonaparte appeared, wanting to be crowned King of Italy in 1805, that its urgent completion proceeded.

Architects Giuseppe Zanoja and later Carlo Amati designed a façade that, while respecting the underlying Gothic structure, incorporates neoclassical elements such as triangular pediments and a more symmetrical and orderly composition.

The five bronze doors that provide access to the interior naves are relatively modern. The oldest dates from 1840, but most were installed in the 20th century:

Each door is a work of art in itself, with reliefs that narrate biblical and historical episodes. The bronze panels contrast beautifully with the façade’s pink marble, and the detail of the scenes is such that it deserves careful observation before entering.

Although some purists criticize that the neoclassical façade breaks the Gothic unity of the ensemble, the truth is that it adds another historical layer to this architectural palimpsest that is the Duomo: a building that, like Milan itself, has known how to evolve without losing its essence.

When you enter inside the Duomo, the first thing you’ll feel is the immense vastness of the space. The cathedral has a Latin cross floor plan with five naves: a central nave flanked by two side naves on each side. This structure is unusual, as most Gothic cathedrals have three naves; the Duomo chose five to expand the temple’s capacity, which can hold up to 40,000 people:

Walking through the Duomo’s interior is like traversing a treatise on sacred geometry made stone: each proportion, each architectural element has a symbolic meaning that medieval builders meticulously designed to elevate the human spirit toward the divine.

The undisputed star of the Duomo’s underground world is San Carlos Borromeo, the 16th-century archbishop who embodied the Catholic Counter-Reformation. His body rests in a theatrical octagonal chapel called the Scurolo, designed specifically for pilgrimage and propaganda. His body lies in a rock crystal urn (a gift from King Philip IV of Spain, no less), dressed in full pontifical vestments, surrounded by silver relief panels narrating his life. Every November 4th, the urn actually rotates to display the saint’s body to crowds of faithful.

Now, the Visconti family founded the Duomo, so naturally they’re here too. Gian Galeazzo Visconti, the duke who ordered the cathedral’s construction in 1386, has his tomb inside, along with other family members.

The most visually imposing monument in the right aisle belongs to Gian Giacomo Medici. The massive mausoleum, sculpted by Leone Leoni, is stunning, except for one crucial detail: it’s completely empty. The central sarcophagus was never made because the Council of Trent’s new austere rules prohibited such lavish burials inside churches.

The oldest resident, Ariberto da Intimiano, an influential 11th-century archbishop, rests in a deliberately reused Roman sarcophagus from the 3rd or 4th century AD.

But here’s the kicker, he wasn’t moved to the Duomo until 1783, right in the middle of the Enlightenment. Why? Cathedral authorities were creating a powerful visual narrative: an unbroken line from ancient Rome (the pagan sarcophagus), through medieval Christianity (Ariberto), to the present day. Above his tomb sits a copy of the Ariberto Cross, the original c. 1040 masterpiece is safely kept in the Duomo Museum.

The Duomo isn’t frozen in time, though. Cardinal Carlo Maria Martini, who died in 2012, proves the cathedral is still actively writing its story…

The Milan Duomo houses more than 3,400 statues, including marble figures, saints, gargoyles, monsters, and decorative elements. It’s the largest sculptural collection of any building in the world. Here are some of the most significant:

The Madonnina is, without a doubt, the most emblematic sculpture of the Duomo and of all Milan. Crowning the tallest spire at 108.5 meters high, this statue of the Virgin Mary measures 4.16 meters and was created in 1774 by sculptor Giuseppe Perego.

It’s made of gilded copper, and its shine is visible from various points in the city. The Madonnina holds one hand raised in a gesture of blessing toward Milan, and for centuries was the city’s highest point. Milanese people venerate her as the city’s protector, and there’s a tradition that no building should exceed her in height (although modern skyscrapers have broken this rule, many place small replicas of the Madonnina on their rooftops as symbolic compensation).

One of the most striking sculptures in the interior is Saint Bartholomew Flayed (1562), a work by Marco d’Agrate. This marble statue represents the martyr saint after his martyrdom: flayed, with his skin hanging over his shoulders as if it were a cloak.

The level of anatomical detail is both disturbing and masterful: you can distinguish muscles, tendons, and veins with surgical precision. The sculptor was so proud of his work that he engraved on the base: “Non me Praxiteles sed Marc finxit Agrat” (“Not Praxiteles, but Marco d’Agrate made me”), comparing himself to the famous Greek sculptor. It’s one of the most photographed pieces in the interior due to its realistic crudeness.

On the main façade, above the central door, stands a statue known as “Legge Nuova” (New Law), created in 1810 by Camillo Pacetti. This female figure carries a spear with a Phrygian cap, symbol of liberty, and was commissioned during the Napoleonic occupation. What’s fascinating is that this sculpture partially inspired Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi when he designed New York’s Statue of Liberty. Although it’s not a direct copy, there are conceptual similarities in the allegorical representation of liberty as a female figure with republican symbols.

The statue of Saint Charles Borromeo, Archbishop of Milan and one of the city’s most venerated saints, appears in multiple locations throughout the Duomo. The most notable is found on the exterior, near the crypt where his remains rest.

Borromeo was fundamental to the Catholic Counter-Reformation of the 16th century and is especially remembered for his work during the plague of 1576, when he remained in Milan attending to the sick while others fled. His austere figure, generally represented with cardinal’s robes and a book, symbolizes devotion and sacrifice.

Inside, near the south transept, stands an impressive statue of Saint Christopher that the Milanese affectionately call “The Giant” due to its monumental dimensions. This 15th-century sculpture represents the patron saint of travelers carrying the child Jesus on his shoulders while crossing a river. The figure measures several meters and is carved from a single block of Candoglia marble. According to medieval tradition, whoever looked at an image of Saint Christopher at the beginning of the day would be protected from sudden death, so its location near the entrance was strategic for the faithful entering the cathedral.

Although technically not statues proper, the Duomo’s gargoyles and chimeras deserve special mention. There are hundreds of these grotesque and fantastic figures: dragons, winged lions, demons, hybrid creatures that defy any zoological classification.

From the terraces you can see them up close and appreciate the unbridled imagination of medieval sculptors. Some have a practical function as drains (the true gargoyles), while others are purely decorative. It’s believed that these monstrous figures had an apotropaic purpose: to ward off evil spirits and protect the sacred space.

The Piazza del Duomo is not only Milan’s geographic heart, but its historical, cultural, and social epicenter. This rectangular square, approximately 17,000 square meters, has witnessed imperial proclamations, political demonstrations, religious celebrations, and today, the daily bustle of millions of visitors who stop here each year to admire the cathedral.

The square’s current configuration is relatively modern. Although the space has existed since the Middle Ages, it was Giuseppe Mengoni who between 1865 and 1877 gave it its definitive form, demolishing the medieval fabric that surrounded it to create an open and monumental space. The white Candoglia marble pavement (the same as the cathedral’s) was installed in 1865 and replaced the old cobblestones.

The most notable building besides the Duomo is the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II, located on the north side of the square. This iron and glass shopping gallery, also designed by Mengoni, is considered one of the world’s first shopping malls and connects the Piazza del Duomo with Piazza della Scala. Its monumental entrance, with a 47-meter-high triumphal arch, architecturally dialogues with the cathedral’s façade.

In the center of the square stands the equestrian statue of Victor Emmanuel II, first king of unified Italy, inaugurated in 1896. This bronze sculpture on a granite pedestal is one of Milan’s most popular meeting points.

The Royal Palace (Palazzo Reale), located on the south side, was the residence of Milanese rulers from the Middle Ages until the 19th century. Today it houses the Duomo Museum and hosts important temporary art exhibitions. Its neoclassical façade, the work of Giuseppe Piermarini, complements the square’s architecture.

The square is also the stage for important events: free concerts are held here (such as the traditional New Year’s concert), sporting celebrations (especially when Milan’s teams win titles), and even fashion shows during Fashion Week.

A curious detail: beneath the square extends a network of underground galleries and World War II air raid shelters, some of which can be visited on special tours. The “Duomo” metro station, one of the city’s busiest, is also located here.

For the Milanese, Piazza del Duomo is simply “il centro” (the center), the absolute reference point from which distances are measured and meetings are arranged. It’s where Milan’s heart beats, where amazed tourists, impertinent pigeons, street vendors, and Milanese people hurrying to work all coexist, all under the eternal gaze of the Madonnina.

TICKETS

When you visit the Duomo in Milan, this ticket gives you access to important attraction. The ticket is valid for three days from the date you…

TRAVELER INFORMATION

The main cathedral and the archaeological area are open every day from 9:00 AM to 6:00 PM. Duomo Milan’s opening hours are the same…

DUOMO MILAN INFORMATION

The Duomo di Milano also known as the Milan Cathedral is an amazing architectural wonder. It is one of the largest Gothic cathedrals…